The Rosetta Stone

Snack: Gather animal crackers, stick pretzels, shelled

peanuts, Cheerios, and any number of other small edibles. Make up a code using

them. You know: one Cheerio is an "A," one peanut is a "B," two pretzels is a

"C," and so forth. On a clean plate, order them into a sentence or short

"picture story." Now eat all your symbols, with a big glass of milk that needs

no translation!

----------------

Supplies:

Foil

Ballpoint pen

Piece of corrugated cardboard

Paper and pencil

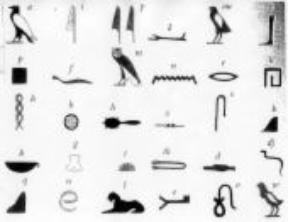

Ancient Egypt used hieroglyphs -

picture symbols - as their means of writing for 3,500 years. The word is

pronounced "hi row glyph," and it means "sacred writings," because most of what

the ancient Egyptians were writing about was what they held to be sacred.

The ancient Egyptians used these symbols, often called

"pictograms," to tell their stories. They wrote about kings and their families,

autobiographies of their heroes, war stories, chronicles of history,

governmental "propaganda," administrative documents, records of expeditions and

explorations, wisdom and philosophy, and much more.

Hieroglyphic symbols included people, animals, birds,

insects, and all kinds of other things. Other symbols related to the sounds of

the language that couldn't easily be pictured, so these were called phonograms (phono meaning sound, and gram

meaning written).

These pictures were painted or written with a reed pen on ostraka (fragments of pottery or

limestone), whitewashed boards, or papyrus. Or they were carved with a chisel in

stone, on buildings, monuments, tombs, pottery and objects in Egypt. The

symbols changed very little over the millennia during which they were used.

The Egyptian hieroglyphic "alphabet" is part of the

afro-asiatic family of languages, with more emphasis on consonants than vowels

(a, e, i, o and u in English). It was based on 24 consonants. Compare that to

the 26 consonants AND vowels in the English alphabet!

It also used many of the same suffixes for certain parts of

speech, more like Arabic than English. Hieroglyphic messages could be read from

left to right, or from right to left, or even upwards or downwards. If the

birds in a given piece of writing all faced to the left, for example, that

meant you were supposed to read that line from the right toward the left - the

opposite of the way we read text in English. To further complicate translation

for us English-speakers, they had separate symbols for certain letters

combinations, such as "th."

Hieratic script

Demotic script

Coptic script

As time went on, other forms of writing came into place in Egypt,

chiefly hieratic script, which was

like a faster "shorthand" of hieroglyphics, the quickly-jotted demotic script, and Coptic, which combined Greek letters with a few demotics to fill in

for Egyptian sounds that weren't found in the Greek language.

So there was a lot to know if you were the one writing the

hieroglyphics in ancient Egypt, or someone centuries later, trying to read what

they said.

And that just made it really hard

for the people who came long afterwards to try to translate what the hieroglyphs

meant, because we lost the "code." From the fifth century until the discovery

of the Rosetta Stone, no one could accurately translate what the hieroglyphics

meant exactly. They could just guess, although the pictures and images are

fairly straightforward, and a lot could be inferred about Egyptian history,

society, religion and agriculture.

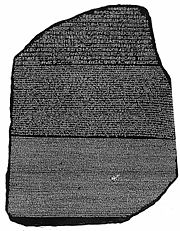

Then, finally, we found the code -

the key - a way to accurately translate. It was a large, flat slab of granite

found in 1799 in a town now called Rashid, located where Egypt's Nile River

flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Greeks had called the town "Rosetta," so

the stone was called "The Rosetta Stone." The reason is was important: it had

the same piece of writing in hieroglyphs, demotic script, and Greek.

Researchers could see how each of those languages was translated into the other

scripts. Voila: accurate translation was possible!

Researchers

believe the stone was carved in 196 B.C. in the time of the Egyptian king

Ptolemy V. It was deciphered in 1822 by the French scholar Jean-Francois

Champollion. Another scholar who helped translate it was the British physicist

Thomas Young. The job was difficult because quite a lot of the hieroglyphic

portion had broken off. The dark bluish-gray slab is 45" tall, 11" thick stone

has been on display in the British Museum since 1802.

Now, just for fun, fold a smooth

piece of foil carefully around a slab of cardboard, and make your own Rosetta

Stone!

Take the paper and pencil, and write

a message that includes your name. Now, under each letter, invent a symbol for

each letter. Now translate your message onto your "Rosetta Stone." Only use the

END of the pen, not the ink part, so that it will appear to be carved out of

the foil. "Write" your message in the foil. Now show only your "Rosetta Stone"

to someone else, and see if they can translate it without anything to go on. If

they can't, show them at least what the symbols are that translate to your

name. If they still can't get the entire message, show them the code.

Have fun! And here's hoping it

doesn't take CENTURIES for someone to figure out your message!